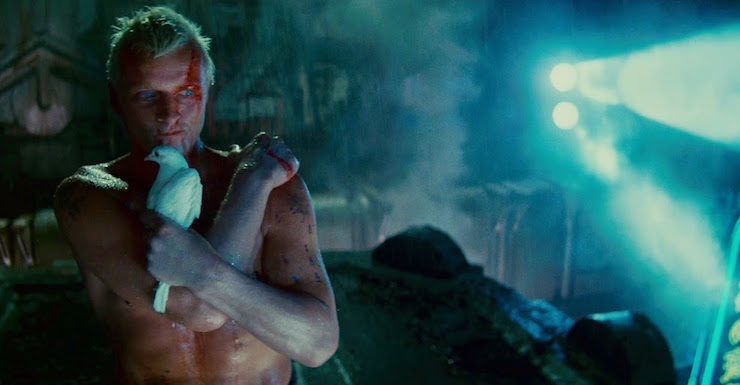

One of the reasons the original Blade Runner film has endured as a classic is its compelling exploration of what it means to be human. As the replicants struggle to extend their artificially brief lifespans, the seminal film probes our notions of empathy, slavery, identity, memory, and death, in profound yet subtle ways.

Blade Runner asks many questions of its audience. Does our capacity for empathy correlate with our humanity? Are we the sum total of our memories, or something more? Do our lives have meaning if no one remembers the things we’ve seen and done when we’re gone? How does questioning someone’s humanity perpetuate the institution of slavery? And what do our fears of a robot uprising tell us about our own human insecurities?

How one answers the film’s many questions is a Voight-Kampff test in itself. Blade Runner, in other words, is a two-hour long Rorschach test—no two people respond alike. We may see ourselves in the replicants, born into broken worlds not of our making, impressed with cultural memories, struggling to find meaning and connection in our all-too-brief lives. This, perhaps more than anything, explains why the film has resonated with so many. We paint our memories and prejudices onto the screen, and what we take from it is uniquely ours.

In this list below, I’ve assembled five works of fiction that have resonated with me in much the same way Blade Runner has, over the years. Each asks profound questions, but doesn’t give easy answers. Each is subject to a multitude of interpretations. And each probes at the boundary of what we think humanity is, only to find that membrane soft and permeable. This list, of course, is by no means complete, and readers are encouraged to add their own suggestions in the comments.

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818)

In Mary Shelley’s classic novel, Victor Frankenstein, a brilliant chemist, mourns the death of his mother, so he begins experiments to restore life to dead matter. He creates an eight-foot tall monstrosity, a living, thinking creature, who escapes from his lab to terrify the countryside. The creation just wants to live in peace with a mate, a female companion like himself. But fearing his creation might make a race of monsters that could destroy humanity, Victor attempts to kill The Creature, with disastrous results. Clearly, many will find direct parallels between the story of Frankenstein and the plot of Blade Runner.

In Mary Shelley’s classic novel, Victor Frankenstein, a brilliant chemist, mourns the death of his mother, so he begins experiments to restore life to dead matter. He creates an eight-foot tall monstrosity, a living, thinking creature, who escapes from his lab to terrify the countryside. The creation just wants to live in peace with a mate, a female companion like himself. But fearing his creation might make a race of monsters that could destroy humanity, Victor attempts to kill The Creature, with disastrous results. Clearly, many will find direct parallels between the story of Frankenstein and the plot of Blade Runner.

More Than Human by Theodore Sturgeon (1953)

Blade Runner fans will recognize the nod to this title in the Tyrell Corporation’s motto. (Which turns out to be prescient; in the film, the replicants regularly exhibit more humanity than their human creators.) In Sturgeon’s novel, we’re introduced to several odd and seemingly unrelated characters: Lone, who has the ability to manipulate minds; Janie, who has the power of telekinesis; Bonnie and Beanie, who can teleport; Baby, with a superior intellect. Together, they merge into a new being, the homo gestalt, formed from their collective consciousness, and the next phase in human evolution. Sturgeon thoroughly explores complex notions of individuality and personal identity in this monumental work of science fiction.

Blade Runner fans will recognize the nod to this title in the Tyrell Corporation’s motto. (Which turns out to be prescient; in the film, the replicants regularly exhibit more humanity than their human creators.) In Sturgeon’s novel, we’re introduced to several odd and seemingly unrelated characters: Lone, who has the ability to manipulate minds; Janie, who has the power of telekinesis; Bonnie and Beanie, who can teleport; Baby, with a superior intellect. Together, they merge into a new being, the homo gestalt, formed from their collective consciousness, and the next phase in human evolution. Sturgeon thoroughly explores complex notions of individuality and personal identity in this monumental work of science fiction.

The Birthday of the World by Ursula K. Le Guin (2002)

In this classic collection from the science fiction grandmaster, Le Guin beautifully unpacks our ideas about gender, sexuality, social mores, and identity in these eight thematically linked stories. Le Guin dissects our binary notions of gender, exploring hermaphroditic societies, cultures where marriage consists of four individuals, planets where the women outnumber men and have all the power, and worlds where the sexes remain highly segregated. After reading The Birthday of the World you’ll want to rethink our oftentimes rigid perspectives on gender and sexual identity.

In this classic collection from the science fiction grandmaster, Le Guin beautifully unpacks our ideas about gender, sexuality, social mores, and identity in these eight thematically linked stories. Le Guin dissects our binary notions of gender, exploring hermaphroditic societies, cultures where marriage consists of four individuals, planets where the women outnumber men and have all the power, and worlds where the sexes remain highly segregated. After reading The Birthday of the World you’ll want to rethink our oftentimes rigid perspectives on gender and sexual identity.

“Exhalation” by Ted Chiang (2008)

In Chiang’s astounding short story, a scientist, puzzled by the mysterious forward drift of several clocks, decides to undergo an experiment to dissect his own brain. But the people in Chiang’s world are not made of flesh and blood, like us, but of metal foil driven by air. Rigging a contraption so that he can peer into his own head, the narrator meticulously dissects his own brain and records the results. It’s literally a mind-bending journey of scientific discovery. Chiang asks, air and metal, or flesh and blood, are we merely the sum of our parts, or is there a ghost in the machine? While the story is ostensibly about a race of mechanical beings, it is, like all the best science fiction, about us.

In Chiang’s astounding short story, a scientist, puzzled by the mysterious forward drift of several clocks, decides to undergo an experiment to dissect his own brain. But the people in Chiang’s world are not made of flesh and blood, like us, but of metal foil driven by air. Rigging a contraption so that he can peer into his own head, the narrator meticulously dissects his own brain and records the results. It’s literally a mind-bending journey of scientific discovery. Chiang asks, air and metal, or flesh and blood, are we merely the sum of our parts, or is there a ghost in the machine? While the story is ostensibly about a race of mechanical beings, it is, like all the best science fiction, about us.

Walkaway by Cory Doctorow (2017)

Doctorow’s novel takes place decades from now, in a world decimated by climate change, where late-stage capitalism has created a few super-rich “Zottas” who rule the world. Advanced 3D printing has allowed people to “walkaway” from the so-called “default” civilization into various free-form societies. In one such society, scientists have developed the technology to download minds into a machine, literally making death obsolete. But the technology is fraught with problems, both physical and spiritual. The artificial minds are barely sane. And they can be copied, replicated, and manipulated as easily as software. If your body dies, but your mind still exists as a computer program, are you still alive? If your mind is copied a thousand times, which copy is the real “you”? Mind-uploading is a common trope in science fiction, but Doctorow handles the subject deftly, suggesting the technology will bring about just as many problems as it solves. After reading Walkway, you’ll rethink your entire notion of what it means to be alive.

Doctorow’s novel takes place decades from now, in a world decimated by climate change, where late-stage capitalism has created a few super-rich “Zottas” who rule the world. Advanced 3D printing has allowed people to “walkaway” from the so-called “default” civilization into various free-form societies. In one such society, scientists have developed the technology to download minds into a machine, literally making death obsolete. But the technology is fraught with problems, both physical and spiritual. The artificial minds are barely sane. And they can be copied, replicated, and manipulated as easily as software. If your body dies, but your mind still exists as a computer program, are you still alive? If your mind is copied a thousand times, which copy is the real “you”? Mind-uploading is a common trope in science fiction, but Doctorow handles the subject deftly, suggesting the technology will bring about just as many problems as it solves. After reading Walkway, you’ll rethink your entire notion of what it means to be alive.

Matthew Kressel is a multiple Nebula Award and World Fantasy Award finalist. His first novel, King of Shards, was hailed as, “Majestic, resonant, reality-twisting madness,” from NPR Books. His short fiction has or will soon appear in Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, Tor.com, Nightmare, Apex Magazine, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Interzone, Electric Velocipede, and the anthologies Mad Hatters and March Hares, Cyber World, Naked City, After, The People of the Book, as well as many other places. His work has been translated into Czech, Polish, French, Russian, Chinese, and Romanian. From 2003 to 2010 he ran Senses Five Press, which published Sybil’s Garage, an acclaimed speculative fiction magazine, and Paper Cities, which went on to win the World Fantasy Award in 2009. His is currently the co-host of the Fantastic Fiction at KGB reading series in Manhattan alongside Ellen Datlow, and he is a long-time member of the Altered Fluid writers group. By trade, he is a full-stack software developer, and he developed the Moksha submission system, which is in use by many of the largest SF markets today. You can find him at online at his website, where he blogs about writing, technology, environmentalism and more. Or you can find him on Twitter @mattkressel.